Partnering for Overseas Development: International NGOs’ Changing Engagement with China

Two parallel trends within the field of international development are converging. The first is the rise of Chinese state-owned enterprises (SOEs) as dominant players in the global infrastructure market, supported by Chinese development finance. Between 2000 and 2014, a sprawling network of Chinese government ministries, provincial governments, and policy banks supplied over $350 billion in official financing. Combining construction capability with ready financing, Chinese SOEs have implemented thousands of infrastructure projects overseas. Beyond Chinese-financed projects, SOEs are diversifying their portfolios and financing by actively bidding on infrastructure projects funded by national governments, foreign commercial and development banks, and private companies.

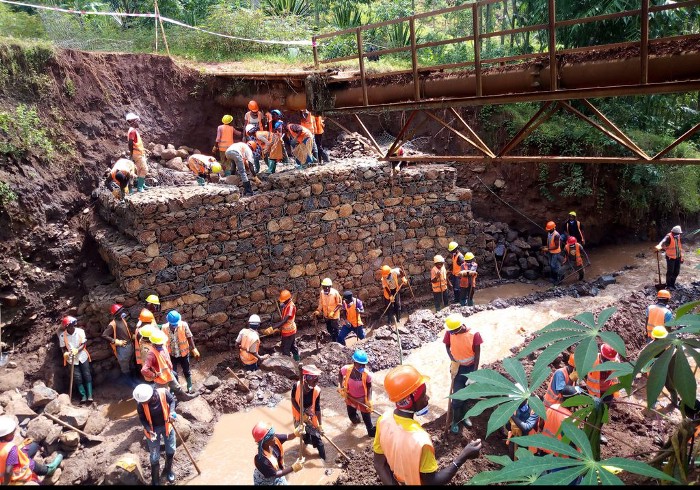

30 June 2020 -- Construction of water infrastructure as part of the IMAGINE (Integrated Maji Infrastructure and Governance Initiative for Eastern Congo) program in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC). Image courtesy of Mercy Corps.

Second, many international NGOs are pivoting from working inside China to partnering with Chinese actors to promote development abroad. Multiple interrelated factors drive this shift: 1) increasing constraints on INGOs operating in mainland China codified by the 2017 Law on the Management of Overseas NGOs; 2) declining supply of international funding for development projects in China, especially as China’s economy has grown; 3) growth in the activities of Chinese philanthropies; and 4) increasing capacity of local Chinese NGOs. To stay engaged with China and maximize impact, many INGOs are remaking their relationships with actors in China from that of donor and recipient to partners in overseas development.

People accessing safe drinking water through the IMAGINE program in the DRC. Image: Mercy Corps.

The convergence of these two trends is catalyzing new development partnerships. INGOs are beginning to contract with Chinese SOEs to build infrastructure projects for international development. One such example is Mercy Corps’ partnership with two Chinese SOE contractors, Sinohydro and China Geo-Engineering Corporation, to build infrastructure for the IMAGINE Program in the Democratic Republic of Congo. This initiative is a multi-year UK government-funded project to improve water access, sanitation, and hygiene and reduce child mortality in the cities of Goma and Bukavu. To our knowledge, the IMAGINE program is one of the first cases of an INGO partnering with a Chinese SOE on a major infrastructure project to promote international development.

Initial interviews with project stakeholders suggest that such INGO-Chinese SOE collaborations may provide important advantages. From an INGO perspective, Chinese SOEs help to stretch limited budgets and often provide the lowest bids in competitive international tenders. Chinese SOEs have the technical expertise necessary to execute INGO-led infrastructure projects, which are typically much smaller than their usual contracts. For INGOs with previous China operations, their staff can apply years of accumulated knowledge and relationships to enhance communication and coordination with Chinese SOEs. In addition, Chinese SOEs also enjoy potential advantages. Though contracts may be relatively small by SOE standards, SOEs view INGOs as reliable partners. SOEs also perceive that collaboration with INGOs could yield reputational benefits and opportunities to expand into new business areas or national markets.

Construction at IMAGINE. Image: Mercy Corps.

But INGO-Chinese SOE partnerships also face limitations and obstacles. INGO projects are too few and small-scale to be a top priority for Chinese SOEs. While Chinese SOEs are interested in working with INGOs on development projects, they also seek to achieve commercial goals. INGOs often have some of the strictest requirements among actors in the development community regarding standards for labor rights, environmental sustainability, gender inclusivity, and health and safety. Ensuring that Chinese SOEs understand and follow these requirements is a key concern for INGOs. Furthermore, INGOs and SOEs’ lack of experience working together can amplify communication issues related to language barriers, contract stipulations, and project standards.

Despite these challenges, INGO-Chinese SOE partnerships are likely to become more common in the future. Chinese SOEs are already attractive partners from a cost perspective, and they will become more competitive as they continue to accumulate international business experience and technical expertise. With mounting uncertainty about future levels of international development assistance due to the COVID-19 pandemic, Chinese SOEs’ cost advantages may become even more attractive to INGOs facing budget constraints in the future.

Finally, novel INGO-Chinese SOE partnerships raise bigger questions about international cooperation and development. How do new and established development actors interact on the ground in developing countries? How do citizens and other local stakeholders perceive development projects involving both INGOs and Chinese SOEs? Prior to COVID-19, relationships between China and other major international donors were already fraught with competition and mutual criticism. Growing friction between China, the United States, and various European states as the COVID-19 pandemic continues could further impede cooperation on development finance. Expanded INGO-Chinese SOE partnerships provide an important opportunity for cooperation between INGOs, Chinese stakeholders, and other actors during a time when development needs are more urgent than ever.

Wendy Leutert is the GLP-Ming Z. Mei Chair of Chinese Economics and Trade at the University of Indiana, Bloomington, and a former An Wang Postdoctoral Fellow at the Fairbank Center. Read her blog post on The Overseas Expansion and Evolution of Chinese State-Owned Enterprises.

Austin Strange will join the University of Hong Kong as Assistant Professor of International Relations in fall 2020, and is a former Graduate Student Associate at the Fairbank Center. Read his blog post on China’s Foreign Aid Beyond the Headlines.

Elizabeth Plantan is a a China Public Policy Postdoctoral Fellow at the Ash Center for Democratic Governance and Innovation at Harvard Kennedy School. Read about her experiences comparing state responses to green activism in China and Russia.